Arguments for a UBI – Conclusion

This post is part of the sequence Arguments for a Universal Basic Income.

Implementation Possibilities

Having addressed the idea of a Universal Basic Income from a wide range of perspectives, it is hopefully not unthinkable that such a policy could generate a similarly wide base of support, given the right framing. If the same policy can appeal to socialists, capitalists, conservatives and liberals alike, whilst being both practical and affordable, it is clearly in need of more attention. The issue is, that it is quite a dramatic policy shift that would be politically untenable to achieve in one fell swoop.

It is understandable that people are wary of dramatic changes to policy, as such things can have unintended consequences that are difficult to predict and also difficult to reverse. The question then becomes how such a policy could be implemented in controlled stages, whilst both maintaining an acceptable level of public support, and avoiding creating an even more complicated system during the transition. This would avoid any sudden, large-scale changes, and therefore be more controllable, less risky and easier to reverse, should the need arise.

Thankfully, there is a way to gradually simplify the existing UK tax code, whilst making it converge with the system of Universal Basic Income described in the Accountant. This sequence of changes also leaves the benefits system largely untouched, simply applying to fewer and fewer people, as the transition progresses. I shall detail this potential sequence of policy changes, to demonstrate that it is indeed possible to achieve the end goal of a Universal Basic Income, without any dramatic changes that could cost excessive political capital, and expose the people and economy of the country to too much risk.

The first few steps do not introduce a Universal Basic Income at all, instead laying the groundwork for its introduction by simplifying the tax code. Starting with the existing 2018-19 UK tax code:

| £11,850 “Personal Allowance” not taxed |

| £11,850 to £46,350 taxed at 20% |

| £46,350 to £150,000 taxed at 40% |

| Anything above £150,000 taxed at 45% |

| For every £2 of income over £100,000, you lose £1 of “Personal Allowance”, which is therefore then taxed at 40% |

This was changed for the 2019-20 tax year. The structure of the tax code remained the same, but the numbers were made slightly friendlier, giving everyone a small tax cut:

| £12,500 “Personal Allowance” not taxed |

| £12,500 to £50,000 taxed at 20% |

| £50,000 to £150,000 taxed at 40% |

| Anything above £150,000 taxed at 45% |

| For every £2 of income over £100,000, you lose £1 of “Personal Allowance”, which is therefore then taxed at 40% |

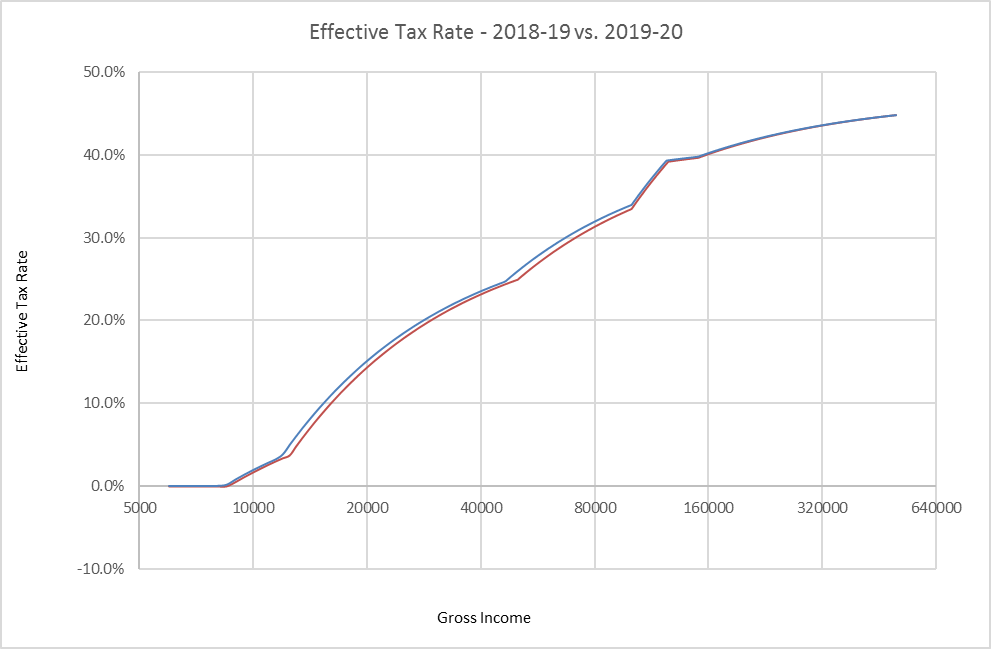

After including the effects of National Insurance, which from 2018-19 to 2019-20 had its lower threshold changed from £8,400 to £8,600 and its upper threshold changed from £46,350 to £50,000, this made the effective tax rate graph change from the blue line to the red line below:

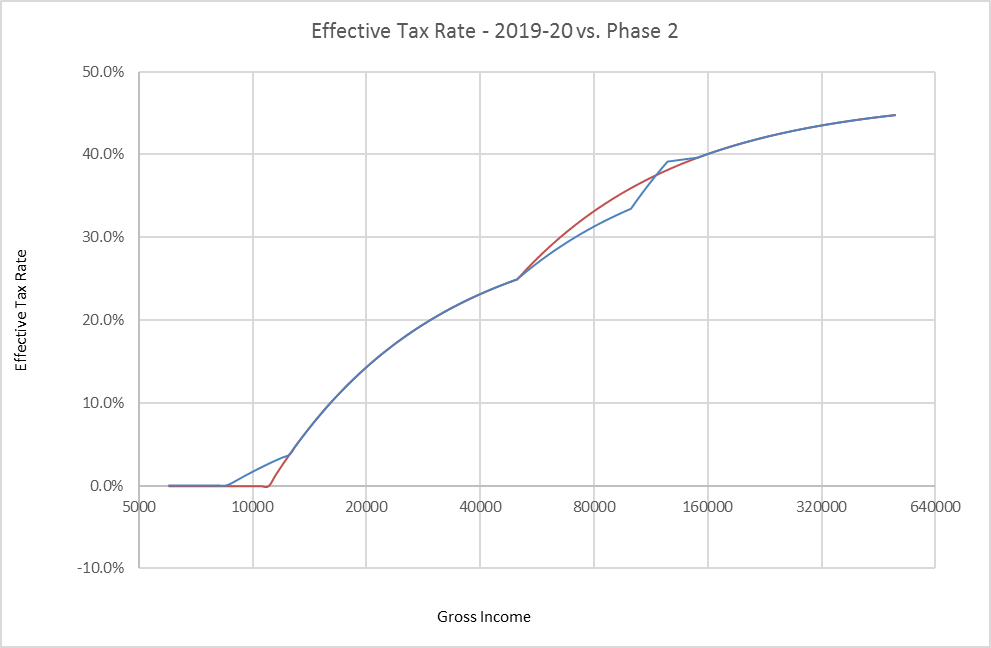

With this as our baseline, the first phase is to make the “personal allowance” universal, removing the phase-out that begins with incomes over £100,000. We clearly want to do this in as revenue neutral way as possible, so that it cannot be painted as a tax cut for the rich, but this does allow us to iron out the bizarre step in the effective tax rate graph, where the marginal rate is temporarily 60%. We can do this by simultaneously removing the phase-out and extending the 45% tax band downwards over the entire 40% tax band, so it starts at £50,000 instead. This changes the tax code to the following:

| £12,500 “Personal Allowance” not taxed |

| £12,500 to £50,000 taxed at 20% |

| Anything above £50,000 taxed at 45% |

The second phase is to merge National Insurance with Income Tax. Because National Insurance will kick in at 12% for incomes over £8,600, while Income Tax only applies over £12,500, we ideally want to find a new value for the “Personal Allowance” that doesn’t change the tax rate for anyone other than those earning less than £12,500, given a new initial tax band of 32%. This can be done by setting the new “Personal Allowance” to £11,000 for our combined tax. National Insurance then drops to 2% for income over £50,000 so this becomes a 47% tax band. The tax code becomes:

| £11,000 “Personal Allowance” not taxed |

| £11,000 to £50,000 taxed at 32% |

| Anything above £50,000 taxed at 47% |

These two changes can be seen on the graph below, again going from the blue line to the red line. Making the “personal allowance” universal causes the change that can be seen between incomes of £50,000 and £150,000 while merging National Insurance with Income tax causes the change for incomes below £12,500:

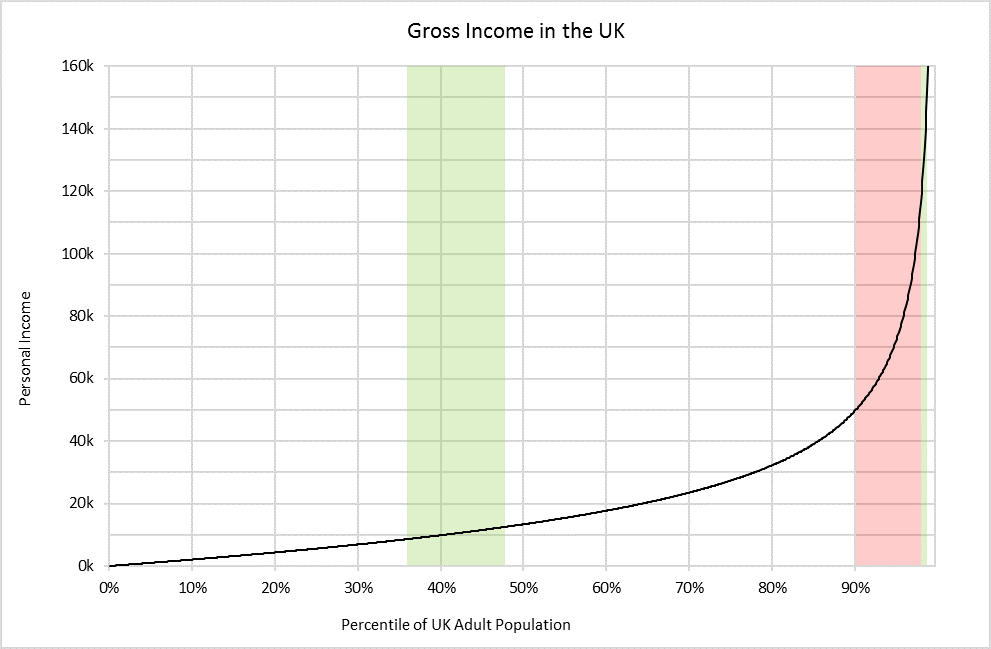

The first and second phases taken together result in an effective tax cut for anyone earning between £8,600 and £12,500 and between £116,500 and £150,000 per annum, and an effective tax increase for anyone earning between £50,000 and £116,500. From a public choice perspective, these shouldn’t be too controversial, as the majority of people would not be affected, and of those affected, more would see a tax cut. By using the tax revenue data from the Realist, we can extrapolate a rough distribution of incomes for the adult UK population, and highlight those populations impacted by the changes. The graph below splits the population into percentiles ordered by gross income, highlighting the percentiles that will see a tax cut in green and a tax increase in red:

From this, we can see that although on the graphs showing effective tax rate against gross income, there looks to be a large range of incomes that would see changes in their tax, these income ranges actually make up a relatively small proportion of the population.

Now that the tax code can be expressed much more simply, we are ready to start gently introducing a small Universal Basic Income. This step will not change taxes for the vast majority of tax payers, and the Universal Basic Income introduced is unlikely to be enough for anyone to survive on, but it is an important conceptual leap that can then be built on. This conceptual leap is simply to replace the “Personal Allowance” with a Universal Basic Income. At a tax rate of 32%, removing the personal allowance of £11,000 would cost each taxpayer £3,500. We can therefore remove the personal allowance from the tax code entirely, and instead pay everyone a Universal Basic Income of £3,500 per year. This is just over £291 per month or £9.58 per day, which whilst not enough to cover all living costs, is a material sum that should make a large difference to anyone that has fallen through the gaps in the benefit system.

Of course, we now need to consider how this interacts with the benefit system, as this is designed to replace some of the money people are already receiving from welfare payments. The most sensible thing to do at this point is to keep the entire welfare apparatus running as before, but once someone’s benefit entitlement has been calculated, only pay whatever amount is above £3,500 (again, excluding health and disability related benefits, which should be transferred to the NHS, and therefore not be affected). Our tax code is now:

| £3,500 Universal Basic Income |

| £0 to £50,000 taxed at 32% |

| Anything above £50,000 taxed at 47% |

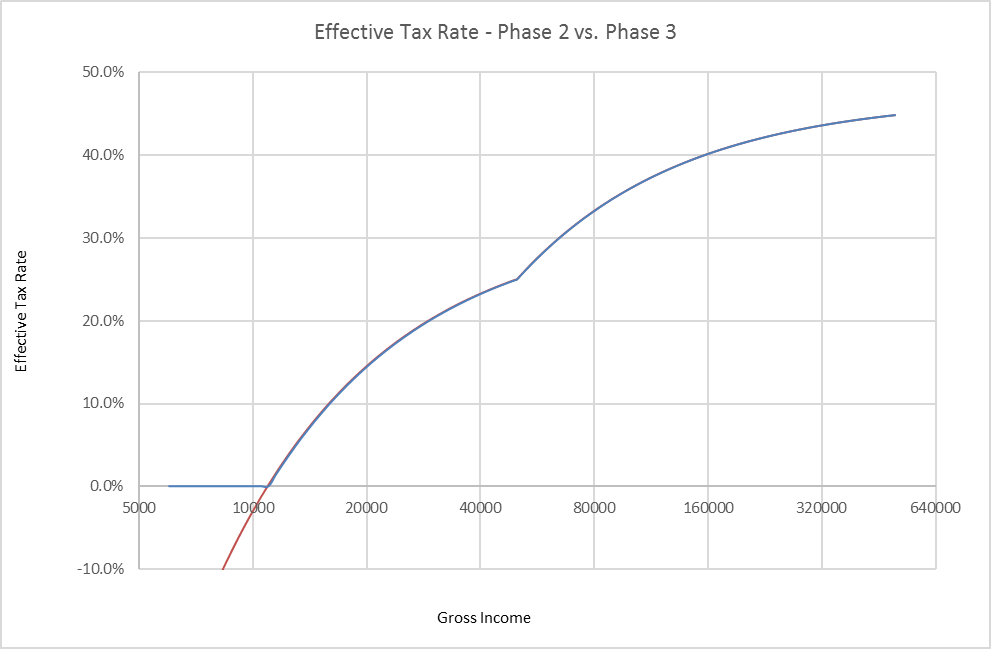

This change is barely noticeable on the graph below, simply extending the curve of the line into the realm of negative effective tax rates, rather than stopping at zero:

With a Universal Basic Income finally introduced, it is now simply a matter of gradually increasing it to the desired level. This can be done in as many or as few stages as is politically viable. Each increase in the level of Universal Basic Income will increase the threshold below which welfare payments are not made, therefore reducing the number of people receiving benefits. This will naturally reduce the caseload for administrators of welfare, as there will be no point in filling out the paperwork for benefits if you are going to be below the threshold for payments anyway. Here I have used 4 further stages to reach the final state:

| Phase | Universal Basic Income | Tax on income <£50,000 | Tax on income >£50,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | £3,500 | 32% | 47% |

| 4 | £4,400 | 35% | 47% |

| 5 | £5,600 | 39% | 47% |

| 6 | £6,800 | 43% | 47% |

| Final | £8,000 | 47% | 47% |

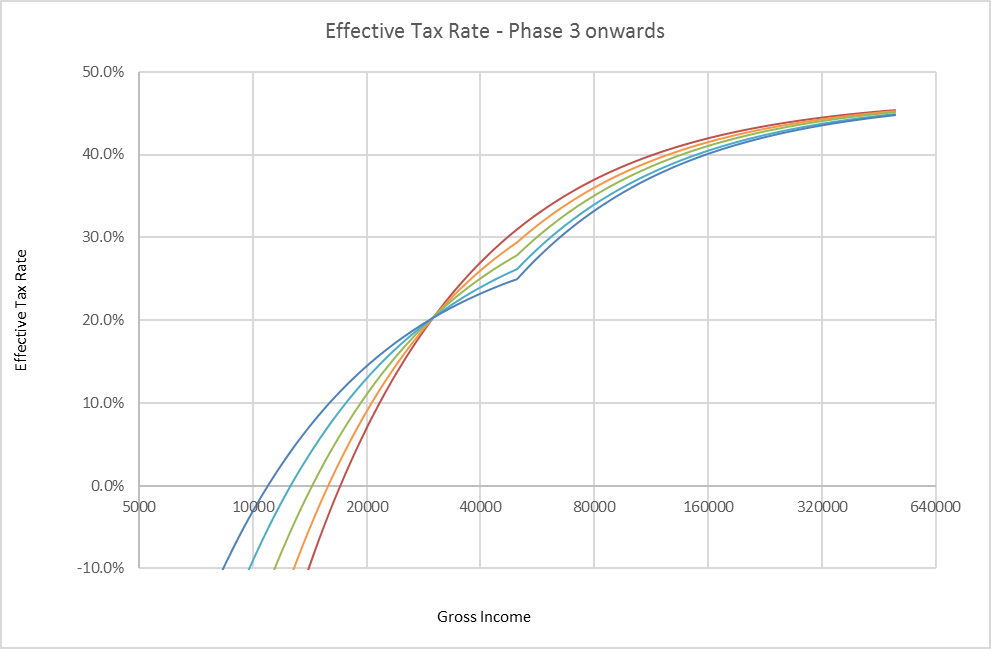

The graph below, starts with phase 3 in blue and ends with the final regime in red:

Each of these phases is a small and simple change, which could be attempted at any time public opinion was sufficiently amenable and could be reversed if any significant negative impacts were to be noticed. They are all effective tax cuts for people earning less than £31,000 per annum, and tax increases for people earning more. At the same time however, it is the headline rate of tax being applied to earnings below £50,000 that is being increased, which should make it difficult to accuse the government of “soaking the rich” with extra taxes.

With a state pension of £8,546.20 per annum in 2018, which will go up by inflation in the future, there will be many elderly people still receiving the amount of this that is above £8,000. If over time the Universal Basic Income increases with inflation as well though, this will be a small difference that could be absorbed within the Universal Basic Income eventually. Aside from this, by the time the final goal of a Universal Basic Income of £8,000 per annum is reached, there will be very few people left who still find it worthwhile to claim benefits. At this point, the government will have to evaluate if there is an appropriate reason for people to be receiving additional benefits above £8,000 per annum each, and act accordingly.

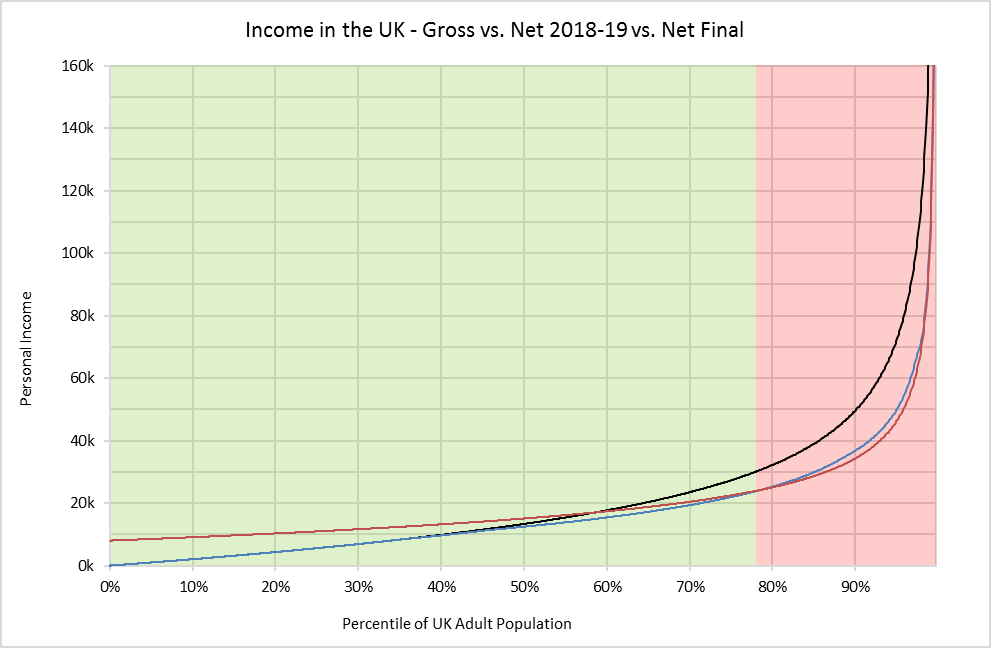

We can again plot this on a graph of income by percentile. This time, as well as showing gross income (black), we can see the net income after tax under the 2018-19 system (blue) and under the final proposed system (red). The green highlighting changes to red at the point where the blue and red lines cross, showing the change from a net tax cut to a raise.

This demonstrates that despite the effective tax rate graph showing tax increases across a wide range of incomes, the increases actually only impact just over 1 in 5 of the adult UK population, with most people being better off. Even for the wealthiest 22%, the graph shows that their net incomes have not been reduced dramatically.

We have already seen that a Universal Basic Income is affordable, as per the calculations in the Realist, and have now demonstrated that it is possible to implement gradually, requiring no great policy leaps. It remains to be seen whether a wide range of people can indeed be won over to the concept of a Universal Basic Income, as the other posts might suggest.

Historically, the UK has led the way in many social reforms but has not made any notable waves in this arena since 1948, when it created the NHS. If the idea of a Universal Basic Income could be brought into the mainstream, perhaps the UK could lead the way again, in becoming the first country to adopt a truly universal social safety net.

8 Replies to “Arguments for a UBI – Conclusion”

I think I would have liked to see a comparative graph which included universal credits marginal tax rate.

I think I would have liked to have seen a comparative graph that included universal credit’s and legacy benefits marginal tax rate.

Thank you for this excellent series of posts. I am actually quite surprised how straightforward you make the realisation of UBI seem. Have you seen these posts which unfortunately make UBI seem pretty unachievable? But that may be a UK vs US thing. https://squareallworthy.tumblr.com/post/175968034577/ubi-masterpost?is_related_post=1

I did encounter the Squareallworthy posts a while ago – from what I can tell, most of the proposals that they review fall foul of at least one of the following:

1. Trying to solve the US healthcare problems at the same time (definitely biting off more than can be chewed in one go…)

2. Trying to make a UBI too “comfortable” – many proposals are in the £12,000 or $15,000 range, which is 50% more than what is being suggested here. For every additional £500 of UBI you want to give out, you have to increase income taxes by around 2.5% (at least for the UK).

3. Making the UBI far too low to replace the programs that it is supposed to be replacing – Dolan’s and Torry’s proposals are for ~£3,000 or ~$4,000 which is effectively funded by halving government payments to the elderly.

4. Trying not to change income taxes – I have seen many proposals trying to fund it with “$Xbn – closing tax loopholes” or “$Ybn – reduce spending on [insert defence program here]” as an attempt to show that it can be done without raising taxes. These always seem wildly farfetched, and require much more sweeping government reform than is realistic. I think it is largely a quirk of the US to view any tax increases as quite such an unpalatable compromise.

5. Trying to be all things to all people – with any policy change it is a trade-off – for some people to be better off, some people are going to be slightly worse off. Rather than accepting this and making sure that the new system is fair, some proposals try to guarantee that everyone will be better off, which is pretty difficult to achieve without some rather bold assumptions. The proposal here for instance will result in slightly higher taxes for people earning >£31,000 p.a., and will likely result in lower take-home earnings for anyone receiving large housing benefit payments (the working poor, living in London) or receiving both state pension and housing benefits.

As far as the UK vs. US thing goes, the next post (the appendix) is an attempt at doing the accountant/realist calculations for the US. I do think it is a harder sell, because their tax regime is less progressive than the UK’s, and their welfare state is less comprehensive.

Thank you, great analysis.

Great work but where is the land dividend? You wrote eloquently about the need to eventually fund UBI from the value that resides in the land that societies use in your article addressed to the philosopher.

Please follow this up and delve into how we might transition to a UBI funded with a dividend derived form the value of the land that societies and economies use

Evolution not revolution! I hope to write about Land Value Tax in the future, but I feel that it is important not to try to change too many things at once, as political will is a very scarce resource.

Out of UBI and LVT, it is difficult to say which would be easier to implement first (no doubt both will be an uphill struggle), but the movement for UBI is currently gathering more steam than the movement for LVT right now. I suspect that trying to implement both at the same time would be doomed to failure, as it would have too much complexity to keep all parties focused on pushing through the required reforms. As the phrase goes: “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good”.

I have been very keen here to keep things as straight-forward as possible, to demonstrate feasibility and desirability to a wide audience. I personally think that a Land Value Tax would be an excellent (and natural) next step, if we managed to achieve a UBI, but focusing on it too heavily risks just adding another non-mainstream concept for people to have to familiarise themselves with.